Modern Challenges in the Settlement of Environmental Disputes: Reflections on ILW 2021

By: Rory Hayes, JD, Santa Clara University School of Law; ILW 2021 Student Ambassador

Climate change is one of the greatest challenges of modern times, and international law plays a vital role in addressing it. At International Law Weekend 2021, held virtually because of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Judge Ida Caracciolo of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea moderated a panel discussing the modern challenges in settling environmental disputes. The panelists included Malgosia Fitzmaurice, Emmanuel Giakoumakis, Meagan Wong, and Jeremy Sharpe.

As iterated during the panel, one of the most important aspects of international environmental law is the development and implementation of noncompliance procedures. The classic kind of noncompliance procedure can be found in the Montréal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES Convention). Both have harsh noncompliance measures – the Montréal Protocol dictates that a caution be issued, followed by suspension while the CITES Convention imposes a suspension of trade rights for noncompliance.

Classic noncompliance measures have given way to a more facilitative approach. One of the panelists, Professor Fitzmaurice, who is a professor of public international law at Queen Mary University of London’s Department of Law, has been performing ongoing research on a new change in noncompliance procedures. While a common approach was to praise attempts to comply and then perhaps issue a caution, this new methodology is more carrot than stick. This shift has influenced more recent international agreements, such as the Paris Agreement and the Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes (Water Convention). Although the Water Convention includes the possibility of suspension, it has never been used. Even the Montréal Protocol has shifted away from its harsh noncompliance measures, so the only convention that still relies on such measures is the CITES Convention.

More confrontational methods of dispute settlement still exist. Emmanuel Giakoumakis, a DPhil in Law candidate at the Oxford University Faculty of Law, is currently conducting research on the assessment of damages in customary international law. According to Mr. Giakoumakis, customary international law provides a basis for compensatory damages for harm to the environment. He mentioned that COP21 expressly agreed that Article 8 of the Paris Agreement does not provide a basis for compensation.

The International Court of Justice’s 2018 decision in Costa Rica v. Nicaragua was the first time it awarded environmental damages. This case centered on a disputed biodiverse protected wetland between the two States. The ICJ found that Nicaragua was responsible for deforestation and other harms, but the two States disagreed on how to calculate the damages.

Figure 1: Map showing the disputed border c. 2010 that was the subject of the ICJ decision. Note that the area marked as “Calero Island” is mislabeled. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Costa_Rica%E2%80%93Nicaragua_San_Juan_River_border_dispute#/media/File:Nicaragua_Costa_R

The ICJ therefore had to wrestle with the inherent problems of conceptualizing environmental damages, which had previously been limited to damage to people, property, or costs required to return the environment to its original condition. This approach had left little room for consideration of the intrinsic value of the environment. While noting that there is no a priori method to quantify environmental damages, the ICJ ultimately decided on a broad, global conception, including CO2 sequestration and loss of biodiversity in its calculation of harm. While Costa Rica was ultimately only awarded $379,000 in damages, the ICJ’s decision is an important milestone for the calculation of environmental damages.

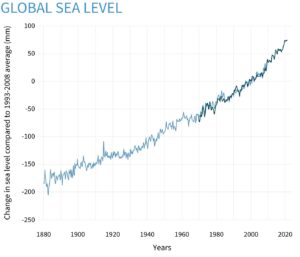

Dr. Wong, lecturer at the University of Essex School of Law, spoke on challenges related to the law of the sea and sea level rise. Sea level rises affect many countries, but delineating responsibility and determining breaches are not easy, especially because the legal obligations are unclear. Surprisingly, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), an international agreement that establishes a legal framework for all marine and maritime activities, does not address climate change or sea level rise. The closest obligation in UNCLOS is a general obligation to protect the marine environment from pollution, leaving State responsibilities on climate change unclear. Similarly, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement are silent on the issue of sea level rise. As a result, there are gaps in obligations regarding the ocean which advisory opinions can help fill. Palau and the Marshall Islands have sought such advisory opinions from the ICJ. However, even if State obligations on climate change were clear, there are few legal avenues for noncompliance because agreements like the Paris Agreement lack clear enforcement procedures for breaches.

Figure 2: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-global-sea-level

The final panelist, Mr. Sharpe, an independent arbitrator and public international law practitioner, spoke on new techniques arising in international investment treaties that could assist in settling environmental disputes. There is an inherent tension in such treaties between the need to protect investments and the public interest in environmental protection, which is likely to lead to more environmental cases filed.

In recognition of this, newer treaties have begun to include three new drafting techniques. One such technique is what Mr. Sharpe called “interpretive guidelines,” which inform tribunals on how to interpret a rule without changing the rule itself. For example, the Trans-Pacific Partnership includes drafting notes about the term “like circumstances,” which can affect how a case is decided. Environmental factors can help distinguish disputes by showing that two entities are not in “like circumstances.”

“Interpretive clarification” is the second technique that puts what Mr. Sharpe described as an interpretive gloss on existing treaties. The language used is often for greater certainty and suggests that the interpretation offered by a State was always the interpretation used.

The final technique, “interpretive indicators,” is language that seeks to tilt the interpretive balance towards the treaty drafters’ preference. This includes so-called “right to regulate” clauses, which carve out the regulatory space the parties are discussing and are influential in tribunal cases regarding the environment. For example, one case found that the “right to regulate” clause subordinated investor interest to the public interest in protecting the environment.

As the harms of climate change continue to mount, effective strategies are required to address international environmental disputes. There are a multitude of existing avenues for settling these disputes and doubtless more will be created, but as Mr. Giakoumakis put it, “Adding more primary rules does not necessarily add much, but the question is: to what extent can we operationalize the existing rules?”