Using Climate Financing as a Guide for Environmental Justice Compensation in Kiribati – Powerless law or law for the powerless? An Environmental and Energy Perspective

Source: Iberdrola.

This piece is part of the American Branch’s first blogging symposium, examining the ILW 2024 theme of ‘Powerless law or law for the powerless?’ from an International Environmental and Energy Law perspective.

Using Climate Financing as a Guide for Environmental Justice Compensation in Kiribati

by Mariah Bowman*

Kiribati’s environmental justice (EJ) issues began as an unreasonable use of a vulnerable community. From 1957 to 1962, the United States (US) and the United Kingdom (UK) used the I-Kiribati residents’ land for nuclear testing without considering their health or future. They did so strategically; operations were carried out with as little care as possible, knowing the I-Kiribati people would not be able to speak or act against them. EJ is about identifying all areas of injustice (human rights violations, economic inequities, gender-based violence – among others) that are only exacerbated by a degraded or polluted environment. The blog aims to present a method to correct the wrongs of the global North, specifically in States with substantially hindered development because of these wrongs, but also where they face the most severe consequences of climate change.

The I-Kiribati people experienced severe discrimination while nuclear tests were being conducted: “[t]here was even less regard for the local community, who were given menial work, degraded,” and described “as ‘scantily-clad people in boats to whom the criteria of primitive peoples should apply.’” During the experiments, the residents would be moved off the island and returned once tests were completed, or they remained and were told to gather under tarps. A young woman and her husband experienced the aftermath: “[w]e didn’t wear protective clothing— we went on deck wearing our normal clothes… When we got home later that day, we noticed that the door and glass windows in our house were broken. The concrete wall cracked, and our pet frigate bird was running around the house blind.”

Kiribati ambassador to the United Nations, Makurita Baaro, spoke at a ceremony for the 2015 International Day against Nuclear Tests and shared the environmental harms committed during the testing: “[i]n Kiribati, when the tests ended, much of the equipment used for the testing were dumped in the ocean or just left behind.” I-Kiribati people have a deep connection with the land and sea; “[t]heir identity is deeply entrenched in this connection,” and disregarding the land and sea as something to use and abuse also dismisses the beliefs of Indigenous communities. Despite concerns over the impacts to the environment and health of the residents, the State has been unsuccessful in their fight for reparations and access to information. Ben Donaldson at the United Nations Association said, “[t]he UK is not only refusing to engage with Kiribati’s work to address the impacts of Britain’s nuclear tests, but it is actively impeding the initiative by withholding vital information.” Kiribati is expected to grow its economy despite the extensive damage done from unwarranted nuclear testing, but now in the face of climate change.

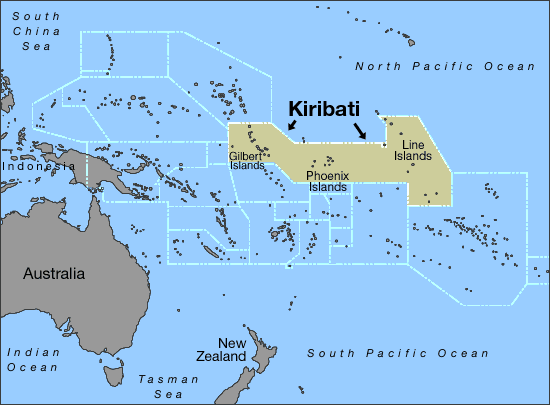

Kiribati is in a remote location and is extremely vulnerable to the consequences of climate change. Sea level rise, combined with erosion and salinization of freshwater, has forced the relocation of villages in Kiribati, and more low-lying islands are at risk of the same. Rainfall has become infrequent, which puts the freshwater lens in danger of saline contamination and permanent damage. This leads to the loss of cultivatable lands and wildlife. In addition, it is predicted that Kiribati’s fish stocks may migrate outside its exclusive economic zone due to ocean warming and acidification, potentially instigating a hunger crisis.

Building resilience is essential to sustain the life of this nation, but this cannot be achieved without attending to the impacts of nuclear testing on the I-Kiribati residents and the State’s environment. It is estimated that Kiribati’s required climate investment in 2040 will exceed 11 percent of its GDP; the State needs a resilient institution that can adopt and preserve adaptation and mitigation strategies, but this is something climate financing does not address.

Kiribati has received external grants for infrastructure, funding from multilateral development banks, such as the Asian Development Bank and the World Bank, and support from the Green Climate Fund for water supply projects. One difficulty in relying on outside funding is completing projects and disbursements. As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) explains, “[t]he main challenges in access to [climate funds] are the procedures required to secure and disburse climate funding.” States must obtain direct access status for the largest climate funds, which involves “fulfilling hundreds of criteria” that are “overwhelmingly complicated and time-consuming.” Vulnerable Pacific Island States, like Kiribati, do not have the time to complete these procedures, wait for disbursement, and finish adaptation projects on schedule with the 2030 Agenda.

As the IMF states, “[t]he impact of climate change is far beyond the ability of any countries to cope with it alone, not to mention small atoll islands like Kiribati.” Considering this, additional problems that were caused by the US and UK’s nuclear testing add to the burden of strengthening the State’s resilience to climate change. This demonstrates a need for climate funding beyond mitigation and adaptation efforts, and the donors need to be further involved in the remediation process. Streamlining the process to obtain climate financing would relieve pressure on developing countries, and donors may be more engaged if they understand where the funds are going and the projects they are tied to. Therefore, it would be worthwhile to consider international funding for cases of environmental injustice.

The plan to remediate EJ issues should also be in accordance with State policies concerning climate change and risk management. For example, Kiribati has a Joint National Action Plan on Climate Change and Disaster Risk Management along with a Climate Change Policy, and all EJ remediation should be a) done according to these policies and b) without inhibiting any work towards mitigation and adaptation. States should also establish the institutional capacity to prevent further environmental injustice and work with donors to improve the system. If an EJ fund were implemented, the disbursement would need a reasonable and predictable timeline. For this to be achieved, granting direct access status should be streamlined, and using an international modality helps provide the oversight required to ensure all parties involved are committed to the program and align priorities.

When these climate funds are solely project-based and do not work with the State’s government directly, it affects the lifespan of the arrangement because the State may not be able to fully implement the adaptation or mitigation strategies following the delivery of the funds. An EJ fund would need all parties (fund managers, donors, and accepting State) to remain involved throughout the remediation process. This will identify problem areas, link these to the problems in the State’s institution, and include the donors and financial manager in the solution.

The EJ fund should not be a system of loans, but should also be treated as something other than a donation box with haphazard disbursements. Each case should be treated as its own funding project but under the umbrella of the EJ fund, meaning the donors and the contributions can be tracked more effectively, and the State can hold donors accountable for the funds not received. For Kiribati, the US and UK should be involved in funding its EJ remediation. Other entities will likely be involved, but there should be a push for these significant figures of the global North to address the impacts of their nuclear testing on States that are most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

However, when other States, financial institutions, or entities contribute to climate financing, the funds are not always directly linked to a specific project or State in need; this is usually decided later. A policy paper from the Center for Global Development found that “climate finance – and especially mitigation finance – is increasingly not being allocated towards specific recipients, and, secondly, when mitigation finance is being allocated to specific recipients, these tend to be middle-income countries rather than the poorest economies.” The effectiveness of the EJ fund would depend on States willingly contributing to specific projects and committing themselves to the planning process and completion of the remediation. Aligning the interests and priorities of donors and the States in need would leverage the funds used in the project.

Many climate financing strategies include debt instruments, which developing countries already need help with. This has become a severe issue. As of 2022, developing countries have reached 11.4 trillion USD in external debt stocks. Therefore, an EJ fund should be solely grant-based and use multilateral funding to diversify the donors. Still, these donors also need to be involved in planning so they have a legitimate interest in remediation and institutional development. The fund should have low compliance costs and increase reliance and trust in the post-program monitoring process. Even for developing states, “[T]he willingness to establish new legal and political institutions, lies in engaging the support of international organizations and other states in their establishment.” Therefore, collaboration is essential in strengthening the State’s institutions and the living standards of the I-Kiribati residents.

It is also important to note that Kiribati has made strides in sustainable practices and information sharing. First, Kiribati has promoted bicycles and electric vehicles for transport, along with low-carbon container/cargo ships and low-energy buildings. Also, the Pacific region has begun improving information systems for predicting natural disasters. These steps are necessary to prepare for further climate change-related events, but the State must also address current problems that may exacerbate future disasters. Kiribati still requires a long-term approach that involves strengthening its institutional and financial capacities.

The purpose of an EJ fund would be to identify the overall environmental justice issues, including who the perpetrators and victims are, the impacts or damage, how it burdens the State, and the changes needed to remediate the problem. In the case of Kiribati, the State has been unsuccessful in its fight for reparations and access to information after the UK and US’ injustice to the I-Kiribati through nuclear testing. Consequently, because many States with a history of colonization have been reluctant to provide reparations, the EJ fund would be a way to preserve the donor’s interest in remaining free from legal obligations but also give the State in need with monetary compensation to address injustice and climate resiliency.

*Mariah R. Bowman is a recent Pace University’s Elisabeth Haub School of Law graduate with additional certificates in International Law and Environmental Law. Bowman has interned for the Indiana Department of Transportation, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Animal Legal Defense Fund, and the Permanent Mission of Costa Rica to the United Nations.

*Mariah R. Bowman is a recent Pace University’s Elisabeth Haub School of Law graduate with additional certificates in International Law and Environmental Law. Bowman has interned for the Indiana Department of Transportation, the US Environmental Protection Agency, the Animal Legal Defense Fund, and the Permanent Mission of Costa Rica to the United Nations.