Asylum in Crisis: Upholding Human Rights During a Pandemic

This post was authored by ABILA Student Ambassador Katherine Griffin, Washington University School of Law ’22.

This post was authored by ABILA Student Ambassador Katherine Griffin, Washington University School of Law ’22.

As part of the American Branch of the International Law Society’s (ABILA) International Law Weekend 2020, in a year when the asylum system has been changed drastically, several prominent scholars spoke on a panel, “Asylum in Crisis: Upholding Human Rights During a Pandemic,” moderated by Sunil Varghese (Policy Director at the International Refugee Assistance Project). The panel was artfully crafted to incorporate a variety of world perspectives: Jaya Ramji-Nogales (Associate Dean for Academic Affairs and I. Herman Stern Research Professor at the Temple University Beasley School of Law) spoke on behalf of the current United States perspective; Afshan Khan (Regional Director for Europe and Central Asia and Special Coordinator for the Refugee and Migrant Response in Europe at UNICEF) illuminated changes in Europe, and Cecilia Jimenez-Damary (UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of internally displaced persons) provided a perspective on Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) specifically.

First, Professor Ramji-Nogales provided background regarding many of the asylum policy changes throughout the past year. During the COVID-19 pandemic, countries around the world have made a strong showing of national sovereignty, “trumping” human rights norms, so to speak. According to Professor Ramji-Nogales, the pandemic has served as a pretext to close down the U.S. border. President Trump’s efforts to destroy the asylum system began in 2018 as he erected a plethora of procedural barriers, making it almost impossible to file for asylum. The administration also heightened standards for the credible fear process—requiring a greater showing for asylees to demonstrate such “credible fear” of their home country as to justify asylum in the United States—and implementing two asylum bans. This year, the pandemic has provided an opportunity for President Trump to shut down the asylum system almost completely. Professor Ramji-Nogales suggested that the future may see COVID-19 testing and quarantine measures for asylum seekers to protect the United States’ public health interest and noted that any such restrictions should be lawful, proportionate, subject to review, and non-discriminatory.

Ms. Khan then provided the European context. Across the southern Mediterranean, authorities have been under extreme pressure to respond to the refugee and migrant crisis for several years. As a result of border closures, countries across Europe’s southern border have been increasingly unable to accommodate the needs of children seeking asylum. There has been no slow down with the COVID-19 crisis, which has a led to some short-term solutions that do not meet international standards. Unfortunately, hundreds of unaccompanied children are homeless and living on the streets. Some are in detention facilities, simply because they have nowhere else to go, facing physical violence. Exacerbating the problem, processing of asylum-related claims has also been slowed by bureaucratic delays, as the pandemic has triggered a heightened sense of urgency for political action. However, the pandemic crisis has also roused a sense of solidarity in the EU to support migrant children. The European Commission has proposed a sweeping new plan to protect unaccompanied children and families with children under 12. Ms. Khan is hopeful about the solidarity expressed in this plan and believes that external monitoring will hold governments accountable.

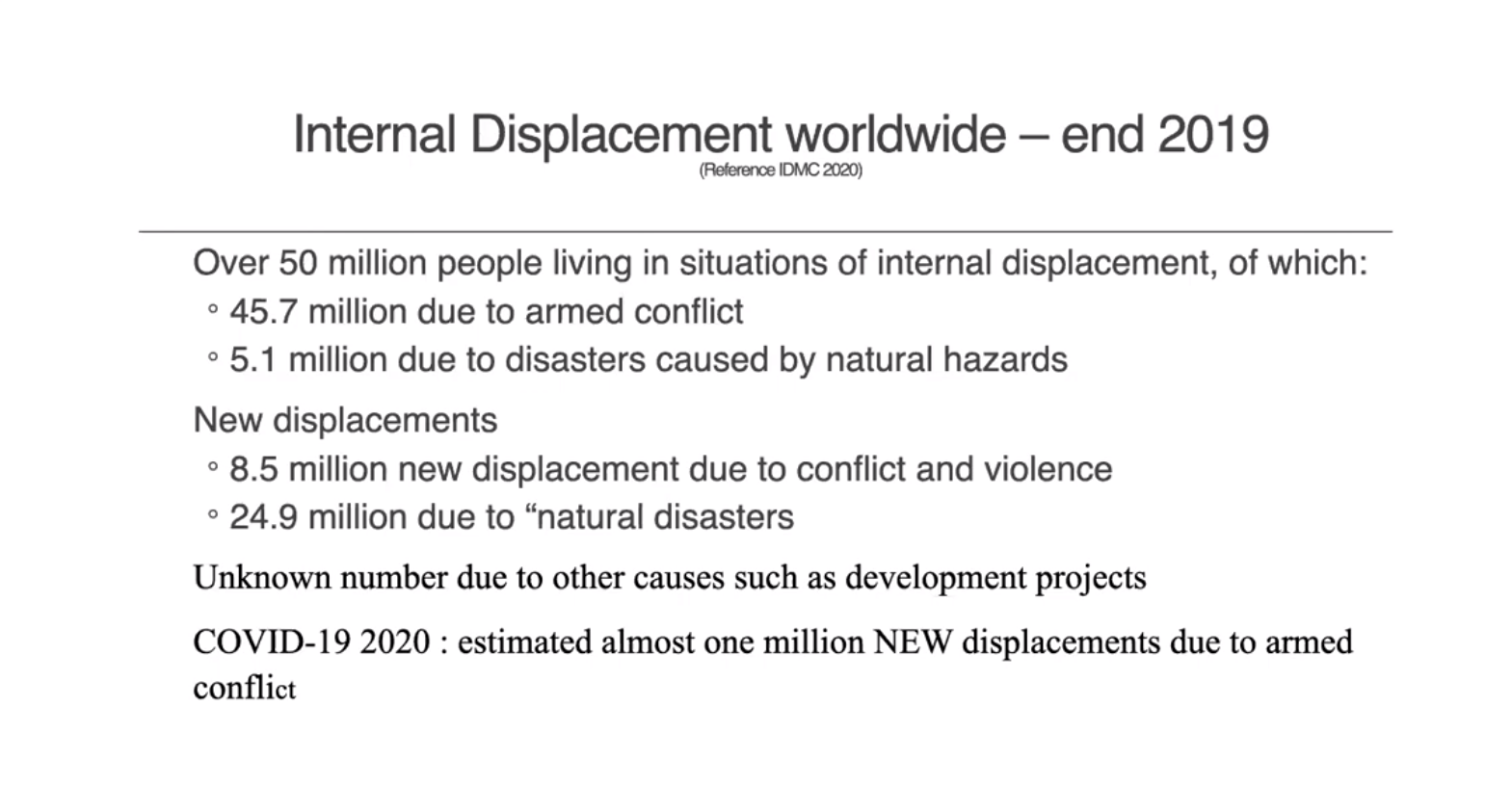

Finally, Ms. Jimenez-Damary highlighted that COVID-19 has not affected peoples’ need to flee internally —in fact, internal displacement numbers have actually increased by 2.5 percent. Internal conflict and political instability have escalated in a number of countries due to, or worsened by, COVID-19, including attacks against civilians and an exponential increase in gender-based violence. Xenophobia is also on the rise; marginalized people accused of spreading the virus are cited in many IDP situations brought to the attention of the OHCHR. Ms. Jimenez-Damary emphasized the importance of strengthening laws protected IDPs, naming El Salvador as an example of a country that has recently done so.

Overall, a delicate balance must be struck between migrant values and health obligations. Both the United States and Europe can afford to implement measures to mitigate the risks of transmitting COVID-19. For example, countries could administer the COVID-19 test, provide safety measures such as masks and sanitation devices, and implement distance learning systems. We need to use our resources to ensure migrants are safe and sanitary. Public health and migrant values are not mutually exclusive—we can protect against contagion and uphold our humanitarian obligations at the same time.