Gwich’in Rights are Caribou Rights – Powerless law or law for the powerless? An Environmental and Energy Perspective

Source: Gary Braasch

This piece is part of the American Branch’s first blogging symposium, examining the ILW 2024 theme of ‘Powerless law or law for the powerless?’ from an International Environmental and Energy Law perspective.

Gwich’in Rights are Caribou Rights

by Kimberley Graham*

“What befalls that caribou, befalls the Gwich’in.”

— Bernadette Demientieff, Chair of the Gwich’in Steering Committee

For over three decades, the Gwich’in have worked to protect their way of life, which is deeply interwoven with Porcupine Caribou. Toward preventing oil and gas development on their sacred lands and the birthing grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd, the Gwich’in have encountered a domestic legal framework that does not directly address Indigenous human rights violations.

Gwich’in-Caribou Relations

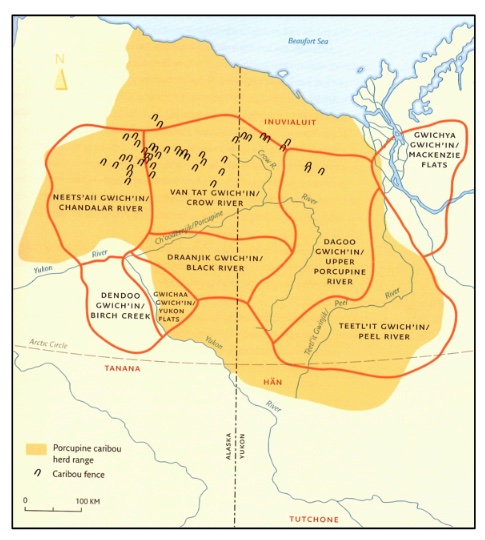

Gwich’in lands across northeast Alaska (United States), Yukon, and North West Territories (Canada) largely mirror the migratory range of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. This is a visual clue of their ‘enduring relationship’ and why they are called the People of the Lands of the Porcupine Caribou.

For thousands of years, Gwich’in were semi-nomadic, basing their movements on the migration of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. Over time, Gwich’in-Caribou relations became interwoven, multi-dimensional, special, and a source of spiritual guidance. Porcupine Caribou are ‘deeply embedded’ in Gwich’in culture and are expressed through various lifeways, such as drum songs, dances, tools, clothes, stories, food, and beadwork. At community gatherings, they recall a time when ‘our ancestor and the caribou were one’ and how, even now, Gwich’in and Caribou ‘hold a piece of each other’s heart.’

Map 1: Gwich’in lands and range of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. Source: Vuntut Gwichin Government.

Importantly, Gwich’in-Caribou relations are the foundation for their multi-decade-long opposition to oil and gas development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (the Refuge). Especially on the Coastal Plain, known to them as ‘the sacred place where life begins’ (lizhik Gwats’an Gwandaii Goodlit), they ‘do not step foot’ there as it is the birthing and nursery grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd. The Coastal Plain is also important ‘for many other life forms’ such as migratory birds, wolves, owls, and arctic foxes, and where polar, brown, and black bears live side by side.

While mainstream narratives have posited the debate about oil and gas development on the Coastal Plain as an energy vs. wilderness issue, for the Gwich’in, it is a human rights and food security issue. This is because harm to Porcupine Caribou means harm to the ‘nutritional, cultural, and spiritual needs’ of all Gwich’in communities and their way of life.

In efforts to protect their interwoven relationship with Porcupine Caribou, the Gwich’in have faced domestic administrative and environmental procedures that ‘do not address underlying discriminatory principles,’ allowing human rights violations to occur. As the following section will highlight, pre-legislative processes to establish the Refuge did not include the Gwich’in.

Establishing the Refuge: A Brief Legal Overview

The history of Gwich’in (and Iñupiat) peoples’ habitation on their traditional lands and their world views, culture, and relationships with wild animals were ‘obliterated’ with the establishment of the Arctic National Wildlife Range (the Arctic Range) in 1960. Between 1959 and 60, no Senate hearings were held in or near Gwich’in villages or camps. Most participants were not Native Alaskans but from far-away cities and states with vested conservation, scientific, sports hunting, mining, economic, recreational, and wilderness interests. The Arctic Range law reflects these glaring omissions: aiming to preserve ‘wildlife, wilderness and recreational values,’ but without mention of subsistence needs of rural Alaskans or interwoven Gwich’in-Caribou relations.

In 1980, the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) was passed. This partly addressed the issue of subsistence rights for local residents — but simultaneously designated the Coastal Plain as ‘area 1002’ — earmarking it for oil and gas exploration and drilling. ANILCA aims to fulfill international legal obligations and conserve wildlife connected to the Porcupine Caribou. However, it remains silent on Gwich’in-Caribou relations. Furthermore, when Porcupine Caribou are referenced, it is only in the context of a scientific study to understand the potential impacts of oil and gas development activities on the Porcupine Caribou.

International Law to Protect the Porcupine Caribou Herd

In 1987, a Treaty between the United States and Canadian governments entered into force on the Conservation of the Porcupine Caribou Herd (the Treaty). The Treaty acknowledges the ‘nutritional, cultural’ and ‘essential needs’ as well as ‘customary and traditional uses’ of the Porcupine Caribou by ‘rural Alaska residents’ and ‘Native users’ who should ‘participate in the international co-ordination of the conservation of the Porcupine Caribou Herd and its habitat.’ To this end, it establishes an Advisory Board to make recommendations for protecting the Porcupine Caribou Herd in their own right. However, the Treaty lacks an enforcement mechanism and does not elaborate on special Gwich’in-Caribou relations. There are also questions about how the Treaty has been adhered to by both parties. Since the designation of the Coastal Plain as ‘area 1002,’ numerous concerns have been raised by Canadian First Nation management and co-management agencies, particularly regarding the potential impacts of oil and gas development on Indigenous peoples and their customary and traditional practices. These concerns include the obligation of the United States to notify, coordinate, cooperate, and consult under treaty-based mechanisms, including, but not limited to, mechanisms established by the Treaty on activities likely to cause disruption to the migration of Porcupine Caribou or their ‘important behavior patterns.’

In 1988, all villages of Gwich’in Nations — from northeast Alaska and northwest Canada — gathered for the first time in over 100 years. At that meeting, they agreed that their fate was tied to the health and well-being of the Porcupine Caribou Herd and unanimously opposed oil and gas exploration and drilling in the Refuge. They reaffirmed this position in 2022 with a Resolution to Protect the Birthplace and Nursery Grounds of the Porcupine Caribou Herd (the Resolution) — and have maintained their stance until today. The Resolution recalls international human rights law, in particular, Article 1 of the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (ratified by the U.S.) to prevent deprivation of subsistence needs and Article 25 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (supported by the U.S. Government) to ‘maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship’ with traditional lands and resources.

In 2017, the U.S. Tax Cuts and Jobs Act became law with a provision mandating lease sales for oil and gas development on the Coastal Plain ‘by not later than 10 years after the date of enactment.’ As a precondition for the sale, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management initiated an Environmental Impact Assessment in 2018. Following an ‘aggressive timeline,’the Record of Decision was published in August 2020 to proceed with the ‘most destructive drilling alternative’ by opening up the entire Coastal Plain for lease sales.

In 2019, the Gwich’in Steering Committee made multiple submissions to the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD), calling for urgent action to stop oil and gas development on the Coastal Plain as domestic remedies ‘do not directly address the human rights of the Gwich’in.’ In re-affirming their ‘cultural, spiritual, and subsistence’ relationship with the Porcupine Caribou Herd, they note previous recommendations from the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous peoples to the United States on the need to address the absence of a domestic framework that ensures access to justice for violations perpetrated on Indigenous peoples lands and territories. Furthermore, parties to the International Convention on All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) must prohibit ‘practices and legislation which may not be discriminatory in purpose, but are discriminatory in effect.’ The Gwich’in explain the ‘discriminatory effect of the U.S.’ oil and gas leasing plan will harm the Porcupine Caribou Herd, encroach on Gwich’in sacred lands, impact the health of the Gwich’in through climate change and pollution, and increase the risk of violence against Alaska Native women.’ Numerous human rights violations under ICERD are cited, including the right to health, education, food security, nutrition, a clean environment, culture, religion, free, prior, and informed consent, subsistence, and women’s safety from violence. CERD responded with a series of letters to the United States relaying their obligations to ‘guarantee the respect of the rights of the Gwich’in,’ including their right to free prior and informed consent. However, responses to CERD by the United States government were not made public. Since 2020, the Gwich’in Steering Committee made several submissions to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights with requests for precautionary measures.

Lease sales were issued in January 2021. But, in June, a Secretarial Order was issued (and upheld) to suspend existing leases on the Coastal Plain. It also directs the US Department of the Interior to undertake a comprehensive analysis of the potential impacts of the Coastal Plain Oil and Gas Leasing Program and ‘address legal deficiencies’ under the National Environmental Policy Act.

The Future for Gwich’in-Caribou Relations

A second lease sale is pending. An environmental review of the oil and gas development plan is underway, due for public release in June, with a final decision anticipated by September 2024. Current leases could be ‘reaffirmed, voided or amended to include additional environmental requirements.’ Meanwhile, the Gwich’in are still waiting for a domestic legal framework that directly addresses their human rights – which are indivisible from the rights and well-being of the Porcupine Caribou Herd.

*Kimberley Graham holds an MA in Environmental Law from the University of Sydney and a BA(Hons) in Natural Resource Management from the University of Melbourne. Graham is an Independent Specialist and Researcher; her research interests include diverse human relationships with animals and nature and how they are reflected in environmental legal regimes and political structures. She is a Member of the IUCN World Commission on Environmental Law, the Global Network for Human Rights and the Environment, and the Research Group on Rights of Nature & Animals.

*Kimberley Graham holds an MA in Environmental Law from the University of Sydney and a BA(Hons) in Natural Resource Management from the University of Melbourne. Graham is an Independent Specialist and Researcher; her research interests include diverse human relationships with animals and nature and how they are reflected in environmental legal regimes and political structures. She is a Member of the IUCN World Commission on Environmental Law, the Global Network for Human Rights and the Environment, and the Research Group on Rights of Nature & Animals.

Deprecated: Method hb_options is deprecated since Highend version 3.7. Use highend_option instead. in /home/abila/public_html/wp-content/themes/HighendWP/functions/deprecated.php on line 611