“Ask not what international law can do for you, but rather what you can do for international law” – Reflections of International Law from Dr. Beth Van Schaack and Judge Richard Goldstone

By Clea Strydom, South African Branch of the International Law Association

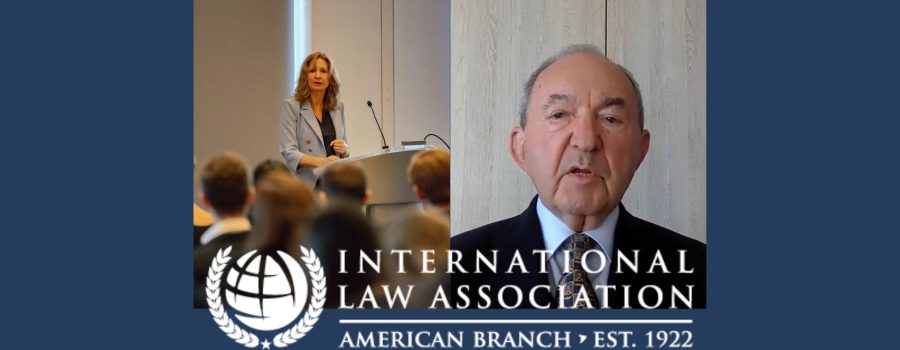

“Ask not what international law can do for you, but rather what you can do for international law,” this paraphrased famous trope, originally said by UN Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs and UN Legal Counsel Miguel de Serpa Soares and used by Dr. Beth Van Schaack, the U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for Global Criminal Justice during her plenary speech at the American Branch of International Law Association’s International Law Weekend 2022 (ILW 2022) captured the essence of the conference as a whole. Held during the American Branch’s centennial year, the conference’s unifying theme of “The Next 100 Years of International Law” invited reflection on the past and future of international law, presenting an opportunity to reevaluate its core features.

Dr. Beth Van Schaack. International Law Weekend 2022, New York.

I was fortunate enough to be invited to ILW 2022 as a representative of the South African Branch of the International Law Association for the second year in a row. However, unlike 2021, when the conference was held online, I had the opportunity to attend the enriching in-person weekend spread across numerous locations in New York, also giving me a look behind the scenes of what it takes to make such an event possible.

The idea that we should be asking what we can do for international law is clearly not lost on the American Branch – International Law Weekend presents an opportunity for academics, practitioners, and experts to consider how they can develop and reinvent international law. And this was especially echoed in Dr. Beth Van Schaack’s speech, which focused on her department’s efforts to strengthen international law, from Darfur to Myanmar, as well as within the U.S. itself.

Beyond the substantive elements of the conference, the organization of the event itself also brought the idea of service to international law to life. The American Branch is one of the most active International Law Association branches, and from what I witnessed at ILW 2022, it is in part due to strong partnerships with sponsors ranging from law schools, law firms, and other international law organizations. ILW 2022 was hosted at the New York Bar Association and Fordham University School of Law, with a Centennial Gala at White & Case LLP and reception at the Permanent Mission of the State of Qatar to the United Nations. This widespread show of commitment to international law is inspiring and could be used as a blueprint for other International Law Association branches.

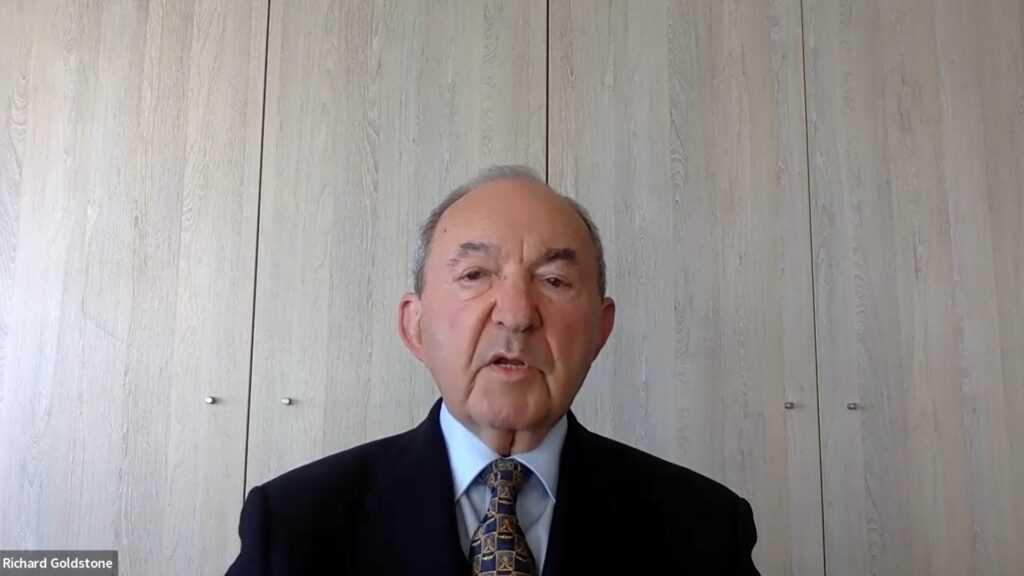

As a proud South African, I was especially drawn to the Outstanding Achievement Award presented to Judge Richard Goldstone, former Justice of the Constitutional Court of South Africa and former Chief Prosecutor of the United Nations International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda.

Richard Goldstone. International Law Weekend 2022, New York.

In his acceptance speech, he reflected on the many ways his career has been shaped by contact with U.S. lawyers, jurists and academics, and many others, especially in terms of the protection and enforcement of human rights and international humanitarian law. In 1959, Goldstone, as a student activist in Apartheid South Africa, was contacted by and met Allard Lowenstein, then president of the United States Student Association, while he was seemingly travelling as a tourist in South Africa. A number of days after this meeting, Lowenstein made headlines when it transpired that the true reason for his visit to South Africa was to smuggle a student Hans Beukes, who had been awarded a scholarship to study in Europe from a Norwegian organization, from what was then South West Africa (now Namibia) under South Africa’s administration in a Volkswagen Beetle across the border after Beukes’ passport was confiscated by the South African government. This was Goldstone’s first interaction with U.S. political activism and just the beginning of his relationship with the country which would assist him throughout his career.

While Goldstone was very complimentary of civil society in the U.S., he did point to the somewhat inconsistent attitude of the U.S. government in the enforcement of international laws prohibiting the commission of serious war crimes.

Towards the end of December 2000, in the dying days of the Clinton administration, Goldstone received a call from David Scheffer – the first U.S. Ambassador-at-Large for War Crimes – who informed him that President Clinton was considering signing the Rome Statute. Relying on the respect Clinton had for Nelson Mandela, Scheffer asked Goldstone whether he would ask Mandela to call Clinton to encourage him to submit to the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court (ICC). Goldstone happily complied with the request and Mandela undertook to make contact. Whether or not a conversation on this matter took place between Mandela and Clinton is not known to Goldstone, but not long afterwards, Clinton told Scheffer to report to the office of Secretary General of the United Nations to sign the Rome Statute on behalf of the U.S. While it would have been a win for international law if the story had ended here, President Bush won the next presidential election and subsequently told his Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security to ‘un-sign’ the vital international criminal accountability statute. To this day, the U.S. is not a party to the Rome Statute.

This Jekyll and Hyde approach of the U.S. to the ICC, depending on the administration in power, also came up in Beth van Schaack’s speech. It is only recently, in June 2020, that the Trump administration imposed, through executive order, sweeping sanctions against ICC officials, specifically ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda and another senior prosecution official, Phakiso Mochochoko, in retaliation to the ICC’s efforts to investigate U.S. personnel in the context of Afghanistan and Palestine. Since the Biden administration came into office, those sanctions have been lifted and attempts to reset the U.S.’s relationship with the ICC have been made, including efforts in Washington, D.C. to ensure that sanctions against the ICC will not be possible in the future. Van Schaack amplified that the U.S. recognizes the importance of the ICC in international criminal justice. Despite this assertion, however, there seems to be no foreseeable chance that the U.S. will sign the Rome Statute.

Keynote Address: The Biden Administration’s Approach to International Justice. International Law Weekend 2022, New York.

This discussion on the U.S.’s relationship with the ICC reminds me of my own country and continent’s tumultuous relations with the Court. While many African countries are party to the Rome Statute and were instrumental in the ICC’s establishment, recent events have led to a call for African States to withdraw from the Court’s jurisdiction, based on a perception of bias against the continent. In response to a question from the audience on the possibility of the U.S. ratifying the Rome Statute, Van Schaack responded that the United States’ relationship with the ICC can be seen along two axis – cooperation and ratification – and that she would rather see cooperation and non-ratification, as opposed ratification and non-cooperation. Putting the false dichotomy aside, I am sure most would agree with her, not just in the case of the U.S. but all States; however, it is a pity that a third option cannot envisioned: ratification and cooperation.

In his acceptance speech at ILW 2022, Goldstone stated that democracy is under siege globally. Covid-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and these two events’ impact on access to healthcare, human rights, international humanitarian law, the global fuel and food supply, etc., has laid bare the international system’s vulnerabilities, especially shining a spotlight on the gaps and flaws in international law, but also its importance.

The events of especially the last three years have also shown us how interconnected we are as a global community; that we are in fact a global village. Therefore, now more than ever we need to ask what we can do for international law instead of asking what it can do for us, to ensure its continued survival over the next 100 years. If I may be as bold to follow Beth van Schaack’s example of modifying a well-known phrase, I conclude with: “It takes a village to raise international law.”

Clea Strydom. International Law Weekend 2022, New York.